New Horizons Spacecraft Hones In On Its Next Kuiper Belt Target

by Sophia Nasr, @Pharaoness

Some 43.4 Astronomical Units (AU) from the Sun, about a billion miles (1.6 billion km) from Pluto, lies New Horizons’ next target: 2014 MU69, a small object in the Kuiper Belt discovered on June 27, 2014 by the Hubble Space Telescope. Nicknamed PT1 (Potential Target 1) by the New Horizons team, this Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) can expect a visit by the New Horizons spacecraft on January 1, 2019.

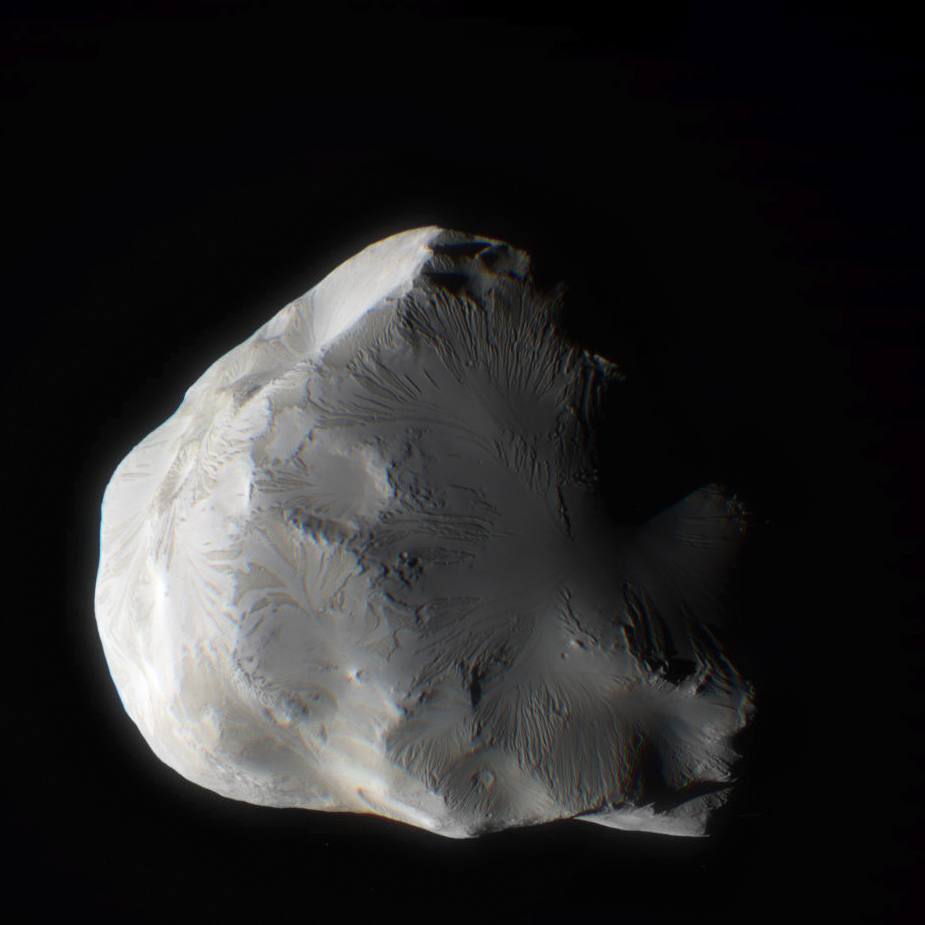

On Tuesday, September 1st, I got a chance to speak via Skype about New Horizons’ next mission with Alan Stern, New Horizons Principal Investigator of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. During the interview, I got some great information about New Horizons’ mission to 2014 MU69. As you would expect, not much is known about this small and remote KBO. "We don’t know much about the target. We know its approximate size, which is somewhere most likely between about 40 and 50 kilometers in diameter," said Stern. While KBO 2014 MU69 seems a small object, it is actually about 10 times as large and 1000 times as massive as a typical comet. In terms of size, 2014 MU69 is comparable to some of Saturn’s smaller moons, like Helene, as Emily Lakdawalla pointed out in an article she wrote in October 2014 (the article can be found here). But as she also points out, the image below is likely not going to be what 2014 MU69 will look like, as Helene is subjected to the dust that pervades the Saturnian system.

2014 MU69 is located in the Kuiper Belt, meaning it’s probably going to be made up of a mix of rock and ice, somewhat like a giant comet. And because of its small size/mass, it’ll probably take on the potato shape of most small objects. As for what we will find, we can’t say; look at the surprises Pluto and Charon brought the world. But don’t expect 2014 MU69 to look like Pluto; the two have very different histories. Stern explained "[w]e know its orbit, and that orbit is from the group of Kuiper Belt objects called ‘Cold Classical KBOs’. Those are objects formed in situ in the Kuiper Belt where they are now." Here’s what this means: 2014 MU69 has a circular orbit that is pretty close to the ecliptic plane, meaning it most likely hasn’t had a gravitational interaction with a larger body that interfered with its orbit. Thus, its current orbit is pretty much the same as it was when it first formed. Pluto, however, did have a gravitational interaction with Neptune when the giant migrated outward in the solar system, an interaction that swung Pluto into its highly inclined and elliptical orbit, and placed it in resonance with the orbit of Neptune such that for every three orbits Neptune makes, Pluto makes two. And, of course, 2014 MU69 is much smaller with a diameter only about 1% that of Pluto, and a mere 1/10,000th Pluto’s mass. These factors mean that the two objects are going to be very different from each other, and hence, we’re in for yet more surprises with this KBO. "[W]e don’t have other properties on it, so we don’t know its rotation period, its color, even if it has satellites. That’s going to be something that we hope to learn while we’re on the way, but if necessary, New Horizons will discover those things when we get there," said Stern.

Why Was 2014 MU69 Selected?

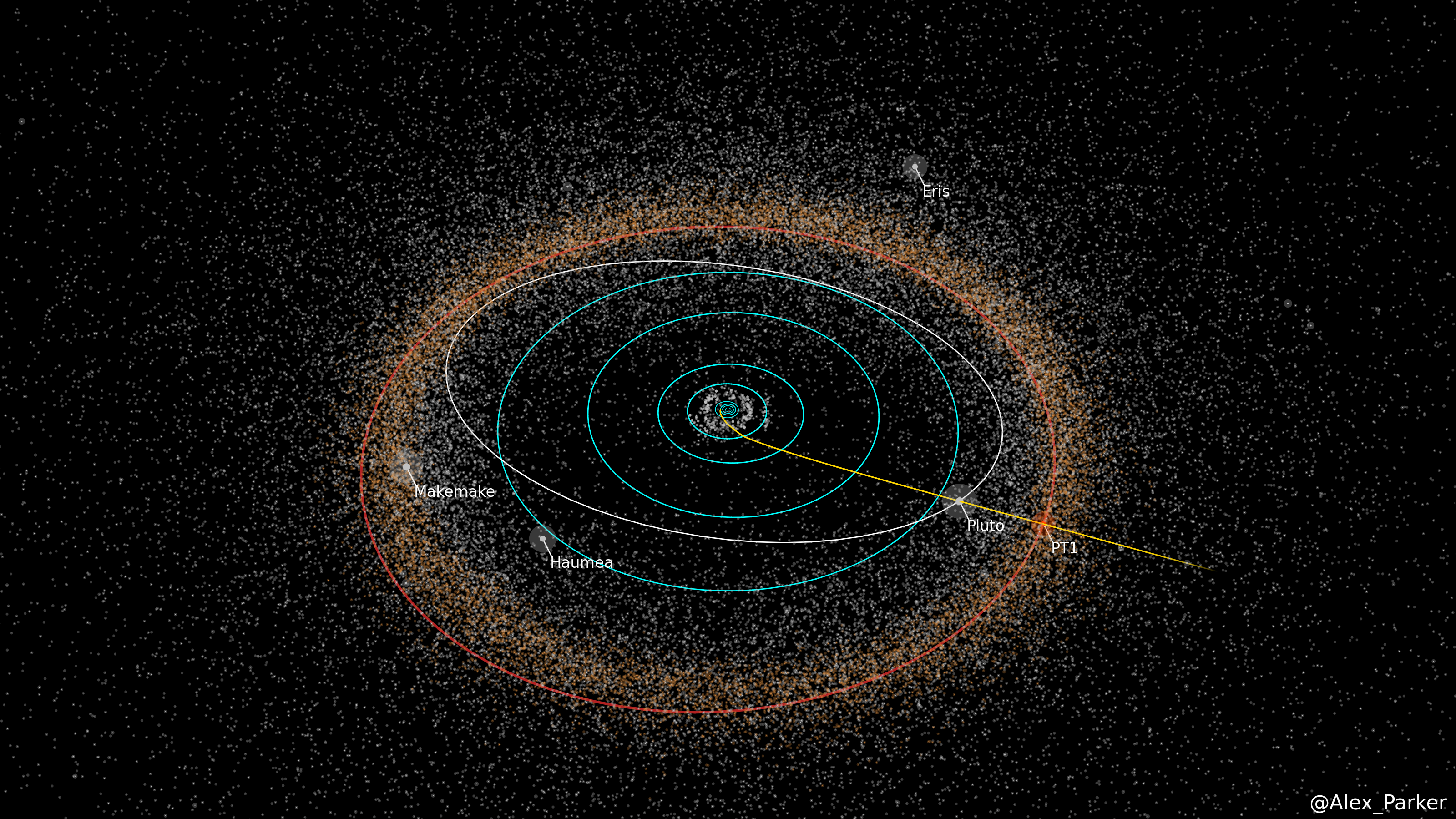

Now, the next question—why 2014 MU69? Why not another dwarf planet, like Eris, for example? Well, the answer is simple—New Horizons is on a specific trajectory that does not come anywhere near the other dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt. With the limited fuel budget onboard the spacecraft, only objects near its current trajectory are within reach. If you look at the graphics below (or click here for an interactive view), you’ll see that Eris, as well as Makemake and Haumea, are all out of reach for the spacecraft.

2014 MU69, on the other hand, is a great target for flyby. It was one of two possible KBOs the New Horizons team suggested, NASA selected 2014 MU69. In the latest press release, Alan Stern said "2014 MU69 is a great choice because it is just the kind of ancient KBO, formed where it orbits now, that the Decadal Survey desired us to fly by." Stern further said "Moreover, this KBO costs less fuel to reach [than other candidate targets], leaving more fuel for the flyby, for ancillary science, and greater fuel reserves to protect against the unforeseen."

A Kuiper Belt Tour

New Horizons will flyby 2014 MU69 with a relative velocity of 14.4 km/s. The flyby of 2014 MU69 will allow New Horizons to get a sample of the diversity of objects in the Kuiper Belt, which was a recommendation made by the 2003 National Academy of Sciences’ Planetary Decadal Survey. Some reasons for this recommendation include the KBO’s size, as well as it being a Cold Classical KBO, as stated by Stern during my interview. 2014 MU69 and Pluto are extremely different objects, so this would allow the New Horizons mission to get a good look at very different objects in a region of the solar system previously unexplored. And because this object could be one of the Kuiper Belt’s elementary units—that is, the stuff that makes up objects in the Kuiper Belt like Pluto—this could offer scientists their first look at the primordial ingredients that make up Kuiper Belt planets. Having received very little heating from the Sun due to its distance, 2014 MU69 could hold a preserved 4.6 billion year old sample of the early solar system. In the latest press release, New Horizons science team member John Spencer of SwRI said "The detailed images and other data that New Horizons could obtain from a KBO flyby will revolutionize our understanding of the Kuiper Belt and KBOs."

Some of the science we can expect New Horizons to do on 2014 MU69 will be much like the science done with the Pluto system. "[O]ur primary three objectives are to map the surface of the KBO, and to map its surface composition from place to place, and to search for an atmosphere around it. But we’ll do many other things, just like at Pluto. We’ll search for more satellites, we’ll take stereographic images, we’ll get thermal data about the surface temperatures, color maps, and much more." The resolution of the data New Horizons will take will be very good—much like the data taken of Pluto. "We know that we’ll get at least as close as we came to Pluto, and that the imagery should be at least as good. The best resolution at Pluto is 70 meters/pixel. But we’re doing a study to determine how much closer we could come. And if we can go substantially closer, we will, and then we will get higher resolution imagery. We’ll also get higher resolution spectroscopy, and other data sets," Stern assured. This is going to be an intensive mission dedicated to deciphering the mysteries that the Kuiper Belt holds in the far reaches of our solar system. The science will fill yet another missing puzzle piece of the story of our solar system, and give us a more complete understanding of its most distant region.

Getting New Horizons to 2014 MU69 will cost the least amount of fuel compared to other reachable targets. But depending on the science done on the KBO, it could use up most of the remaining fuel. "[W]e have about 36 kg that are in the tank now. That’s about half the fuel tank, half the original supply. We know that we will use approximately 20 kg, as a minimum, to conduct the KBO mission. But we haven‘t decided on what other kinds of science we’ll be doing along the way to the KBO," said Stern. The science done along the way will cost fuel, and only when that science is decided will it be known how much of the remaining fuel will be used. Some things that could be done along the way include looking at "other distant KBOs", said Stern. He further commented on how these decisions will be made, and said that we can expect to know by the end of this year or January what observations New Horizons will be doing along the way. "We’re actually conducting about 20 separate studies of the Kuiper Belt mission right now, and I won’t have the answers until the end of the year or January, because these are technical studies, and they’re being carried out in parallel with conducting all the scientific data analysis and operating New Horizons," said Stern.

Because of the amount of fuel required to get New Horizons to 2014 MU69 and perform selected science missions, the spacecraft probably won’t have enough fuel left to visit any further KBOs. But Stern wasn’t so quick to discount any possibility of there being another mission. "That’s to be determined," he said. "[I]t’s not impossible, and we have committed to making a search for still farther KBOs in the coming years."

As New Horizons travels further out into the outskirts of the solar system, it will perform four maneuvers to adjust its course to 2014 MU69. These maneuvers will be performed in late October to early November. And if that’s too long to wait for, fear not—New Horizons will be sending back new data from the Pluto flyby on September 5th. "You should expect to see new data next week, and the following week, and continuously, or regularly, for about a year," Stern assured. And after that, the world will await yet again for just over three years for yet another introduction to a new type of object—the Cold Classical KBO that is 2014 MU69.

Sophia Nasr is an astrophysics student at York University. Actively involved in the astronomical community at York U, she is the President of the Astronomy Club at York University and a member of the team at the York University Observatory. She also is involved in university projects, and holds a position in research on dark matter at York U. Holding scientific outreach dear, Sophia is actively involved in social media outlets such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, where she shares with the world her passion for the universe and how it works.

Sophia Nasr is an astrophysics student at York University. Actively involved in the astronomical community at York U, she is the President of the Astronomy Club at York University and a member of the team at the York University Observatory. She also is involved in university projects, and holds a position in research on dark matter at York U. Holding scientific outreach dear, Sophia is actively involved in social media outlets such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, where she shares with the world her passion for the universe and how it works.