The Icy Frozen Plains of Tombaugh Regio

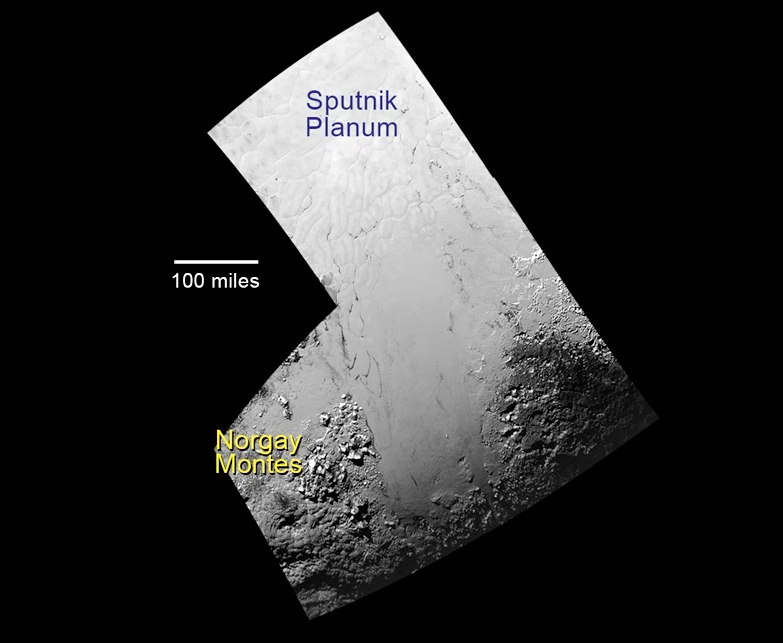

The newest close-up image of the surface of Pluto shows a vast, icy plain void of craters that is possibly still being shaped by active geological processes. The region, which is located in the center left of Pluto’s vast heart-shaped feature - informally named Tombaugh Regio - and just north of Pluto’s icy mountains, appears to be no more than 100 million years old.

"This terrain is not easy to explain," said Jeff Moore, leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging Team (GGI) at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. "The discovery of vast, craterless, very young plains on Pluto exceeds all pre-flyby expectations."

We are seeing amazing complexity and stark contrasts on Pluto with regards to geology. To illustrate this stunning landscape, the mission team released a video showing a flyover of Pluto’s icy mountains and frozen plains. The scene has a total width of about 400 kilometres (250 miles) and features soar as high above the terrain as the Rocky Mountains do on Earth. The video was created from images with a resolution of 400 meters per pixel.

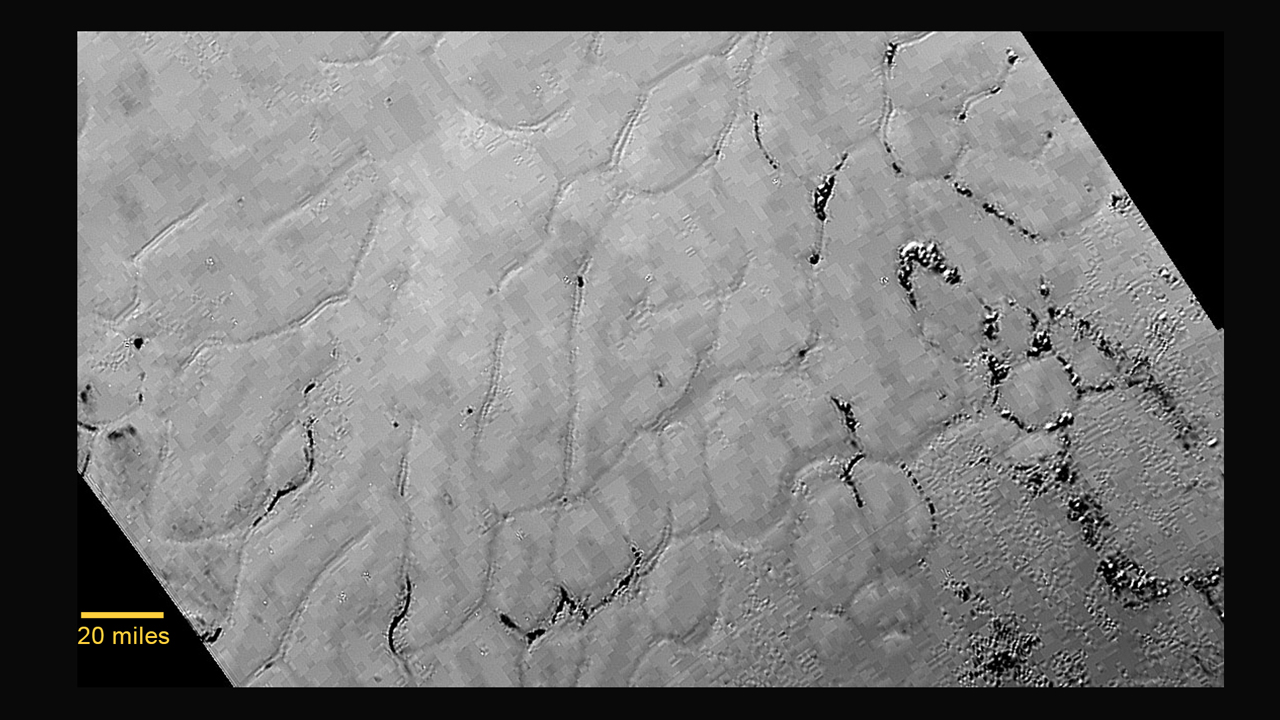

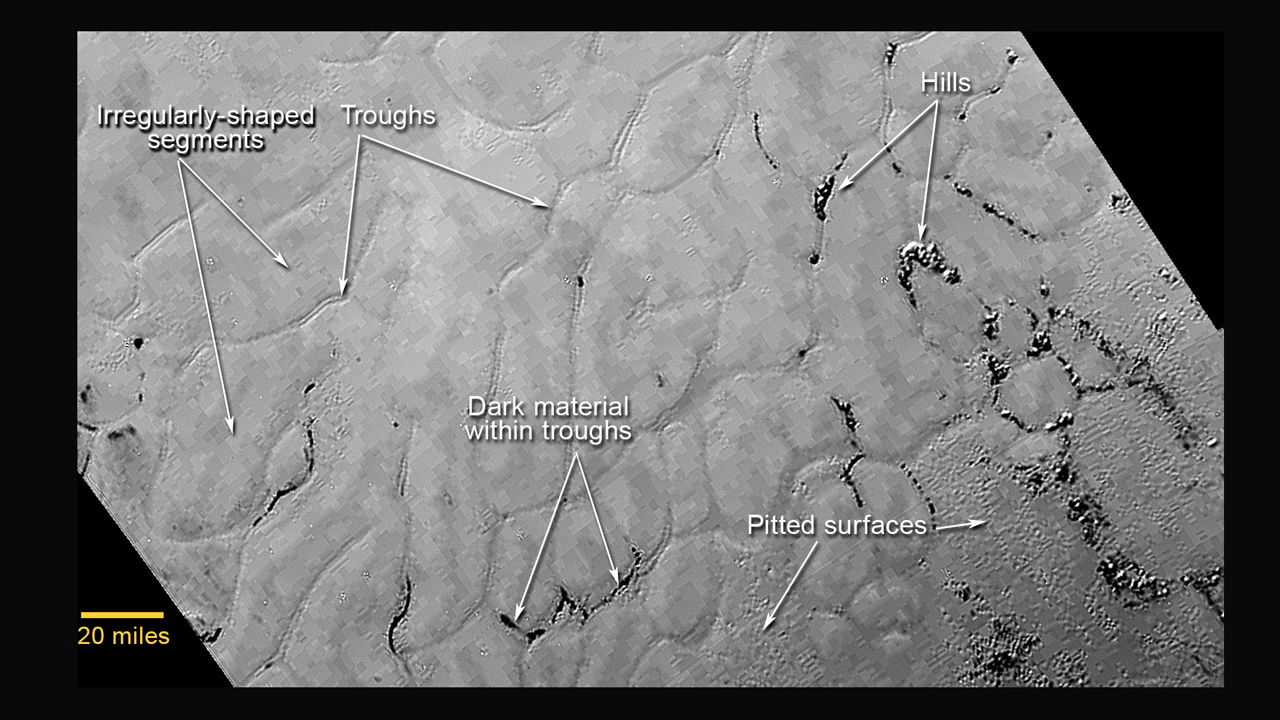

The frozen plains of Pluto - informally named Sputnik Planum after Earth’s first artificial satellite - have an interesting story to tell. First, the lack of craters indicate that the region is no more than 100 million years old and possibly still being shaped by geologic processes today - it could be a week old! Second, the surface is broken up into polygonal segments resembling frozen mud cracks on Earth, each about 20 kilometres (12 miles) across, and ringed by shallow narrow troughs.

Scientists have a couple of working ideas as to how these polygonal segments were formed. One possibility is that the polygons are signs of convection, similar to a pot of boiling water, occurring within a surface layer of frozen carbon monoxide, methane, and nitrogen, driven by moderate heat from the interior of Pluto itself. The segments might also be the result of the contraction of surface materials, similar to how mud dries and cracks.

Some of the troughs surrounding the polygonal segments have darker material collected within them, while others are traced by enigmatic clumps of hills that appear to rise above the surrounding terrain. Scientists don’t know what created these hills. They could be material pushed up from under the cracks or erosion resistant knobs that stand out as the surface around them is being eroded and lowered. In essence, these could be features that are emerging from erosion that is lowering entire plains.

On the lower right of the image, the surface appears to be etched by fields of small pits that may have formed by a process called sublimation, in which ice turns directly from solid to gas, just as dry ice does on Earth.

Below is a three image mosaic of Pluto’s amazing landscape at a resolution of 400 meters per pixel. The young flood plains make up the upper portion of the mosaic, ice mountains (informally named Norgay Montes for Tenzing Norgay, one of the first two humans to reach the summit of Mount Everest) on the lower left, and large scale pitting on the right side.

Some of the craters appear partially destroyed, perhaps by erosion processes, other parts of Pluto’s crust looks fractured, indicating tectonic forces. The presence of icy mountains also indicates some type of mountain building process on Pluto.

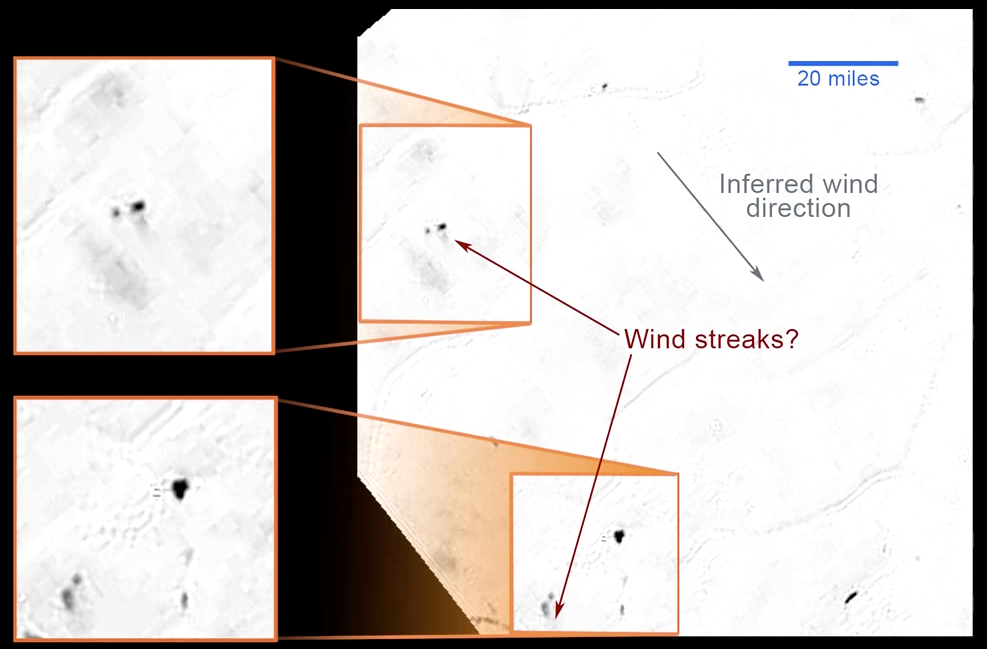

Even more tantalizing to me, on the north west area of the mosaic, Pluto’s icy plains also show a series of dark smudges or streaks that are a few miles long. These smudges are all aligned in the same direction and may have been produced by winds blowing on Pluto’s icy surface. On Mars and Earth, similar features (what scientists call wind streaks) are produced when prevailing winds cause erosion or deposition of material behind topographical obstacles.

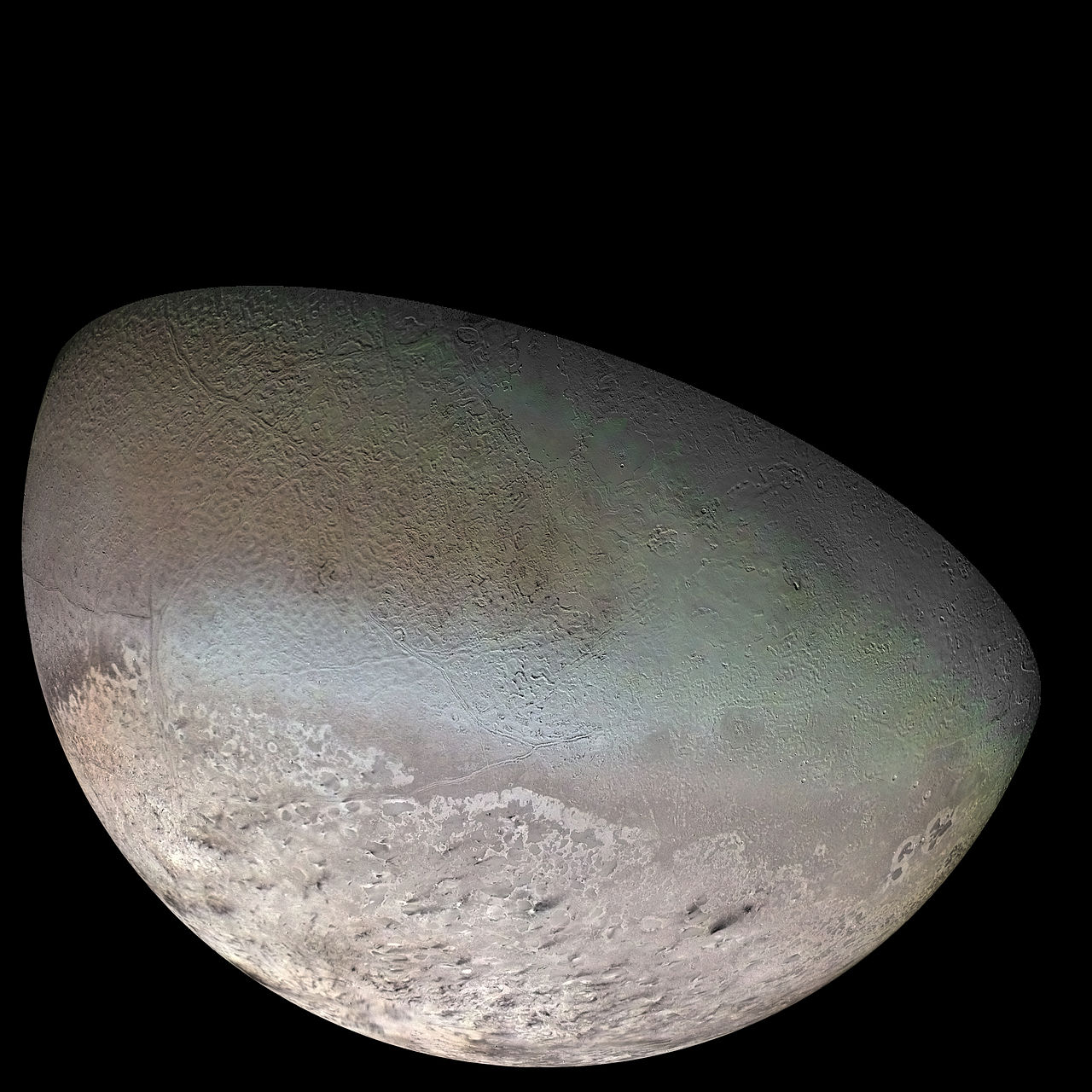

More speculatively, the dark streaks may be plume deposits associated with geysers, like those found on Neptune's icy moon Triton. On Triton, the geysers shoot dark material high into Triton's atmosphere. This dark plume then settles back down to Triton's surface. If there are geysers or plumes on Pluto, they have not been spotted yet. But mission scientists will be looking for them in higher resolution imagery that still needs to be downloaded from the spacecraft.